I’ve been finding that writing LinkedIn posts and articles can be kind of addictive; it’s the same way I used to feel about posting on Facebook in the earlier days of social media. Except on LinkedIn it’s more like shouting into the void, fervently hoping the void will give back – in likes, reposts, maybe even a job offer or a lucrative business deal…

But anyway, today I want to discuss an issue I see with a lot of LinkedIn posts.

Many posters write like this.

Short, punchy sentence fragments.

With dramatic pauses randomly interspersed.

And buzzwords, of course.

Words like ‘clarity’.

Words like ‘presence’.

Words in repetitive patterns.

Ending with some dramatic aphorism, maybe over two lines.

And usually a question to tempt the reader to engage - you’ve seen posts like this, haven’t you?

Now, of course writing techniques like these serve a purpose and we all use them now and again. But I think it’s worth asking: Is this a good way to write posts? Why is this happening? And what should we do about it?

Is this a good writing style for LinkedIn posts?

The clear answer to this is no. I can’t emphasise that enough! I’m obviously late to the party here, because posts in this style have spawned their own label as ‘broetry’ (Lorcan Roche Kelly coined the term in 2017!) and better writers than me have been dissecting the flaws of this writing style for many years. So I’ll just add that in my experience, when I see a post like the above, it creates an immediate and profound sense of detachment that fatally undercuts whatever the writer was trying to achieve; and often, my first and lasting impression is ‘this person just tried to sell me something’.

Why? Because the writer used a clearly unnatural style of communication that dished out their insights in a performative, theatrical, patronising style, sacrificing conceptual clarity (sorry) and detail for lofty, quotable soundbites. Even that slightly strange colleague of yours who’s obsessed with Star Wars wouldn’t speak to you like they’re Master Yoda if you went to them for some advice, because if they did, you’d be left with the impression that they didn’t engage with you on your level or take your ideas seriously. (Uh, if that’s you, may the Force be with you, friend…)

Why is this happening?

The standard explanation is that broetry is a popular style in LinkedIn posts because (1) short sentences are easy to read and digest and (2) it maximises dwell time – the amount of time a reader spends engaging with a post – because the reader has to scroll through all the added whitespace. LinkedIn’s recommendation algorithm is thought to favour higher dwell time. This apparently came about because some posters were getting together into groups, or ‘pods’, to bombard each other’s posts with likes and comments, in order to game the algorithm without actually engaging seriously with the content of posts, forcing LinkedIn to tweak the algorithm to discourage such behaviour.

But I wonder if there’s another dynamic at play as well. LinkedIn users are constrained by the need to present their most professional, ‘workiest’ self on the site. Since posts can be read by colleagues and current/potential employers, it can feel like the stakes are sky-high: posting anything that might be considered contentious becomes a gamble, and getting it wrong can result in a permanent stain on your reputation or that of your organisation. And things like ‘cancel culture’, the backlash against ‘woke’ and ‘DEI’, and other manifestations of political polarisation don’t help either, by ratcheting up the fear-factor. All this makes people risk-averse, and then they’re inclined to adopt a bland, inoffensive messaging style, rather than attempt a critical analysis or a personal take on a topic.

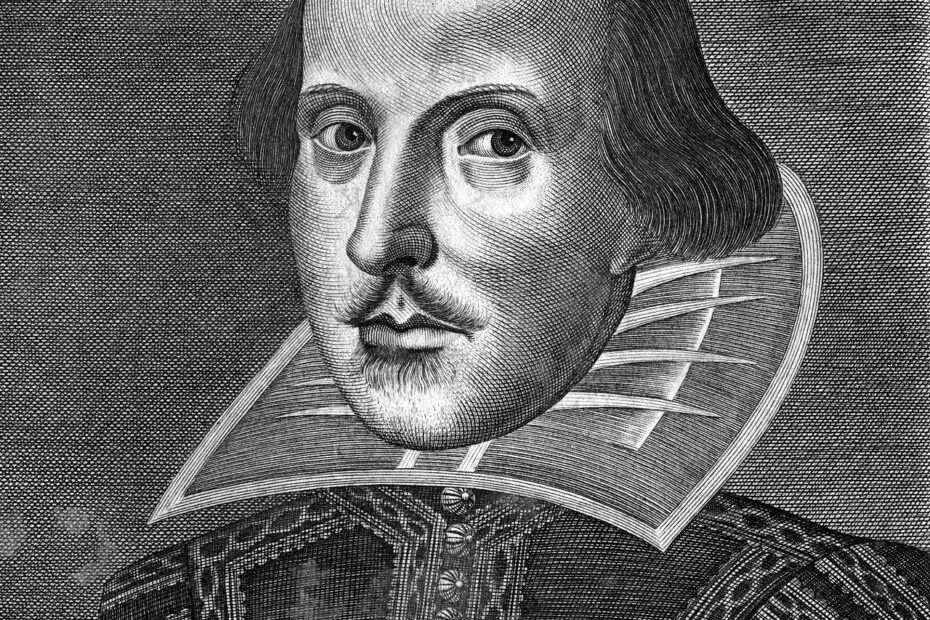

Broetry, then, as a highly poetic writing style, becomes an aesthetic choice that shields the writer from scrutiny by making their insights sound cosmic, timeless, and universal, while at the same time abstracting away details that a critic might use to interrogate what’s actually being said. After all, nobody expects Shakespeare to provide a detailed list of academic references at the end of his sonnets, do they?

What should we do about it?

Let’s take it back to what the authors of posts are trying to achieve: clear, direct communication, perhaps to tell an interesting story, promote a product or service, provide information or just entertain. Well, there’s already lots of resources on how to write effectively out there. So maybe we should start by directing ‘broets’ to these resources – see the ‘further reading’ section for some examples.

I suppose I should caution that, in my experience as an amateur poet (occasionally published, thanks for asking!) who used to engage a lot with the online poetry community, a minority of writers really hate receiving critical feedback on their writing (especially if it’s unsolicited – even though LinkedIn posts constitute an essentially public forum where critique ought to be expected). So providing criticism sensitively is important too.

However, I believe the case against broetry on the grounds of ineffectiveness is so strong that we should encourage people to stop using it and to think more consciously about how they write (and doubly so if people are using generative AI to write posts!). Even though a broet’s LinkedIn metrics may show that engagement on their posts is high, in the long term the broet, wielding their corporate abstract expressionism like Jackson Pollock, risks alienating a large chunk of their audience.

Further reading

- Carina Rampelt, 2020. Why You Should Avoid the Broetry Writing Trend. https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/social-media-content/why-you-should-avoid-the-broetry-writing-trend. A short but still great summary of what broetry is, why people use it and what you can do to write more engagingly.

- Carina Rampelt, 2025. Dead broet’s society: The story behind the strange and bewildering trend that’s eating LinkedIn. https://fenwick.media/rewild/magazine/dead-broets-society-behind-the-strange-story. A deeper dive by the above author into what makes a post a broem, the history of this style of posting, and many examples of how to write more effectively.

- Emily Stewart, 2024. The shame of LinkedIn: Why posting on the site feels so embarrassing — and how to overcome the cringe factor. https://www.businessinsider.com/linkedin-cringe-how-to-post-new-job-hiring-resume-2024-3 [paywall]. A personal discussion of the downsides of posting on LinkedIn, with some suggestions for making it less awkward.

- Plain English Campaign. https://www.plainenglish.co.uk. The website of the Plain English Campaign, which promotes the use of plain English (free of jargon and confusing language) and offers editing and training to organisations. Their free guides, such as the ‘How to write in plain English’ guide (https://www.plainenglish.co.uk/free-guides), are useful.